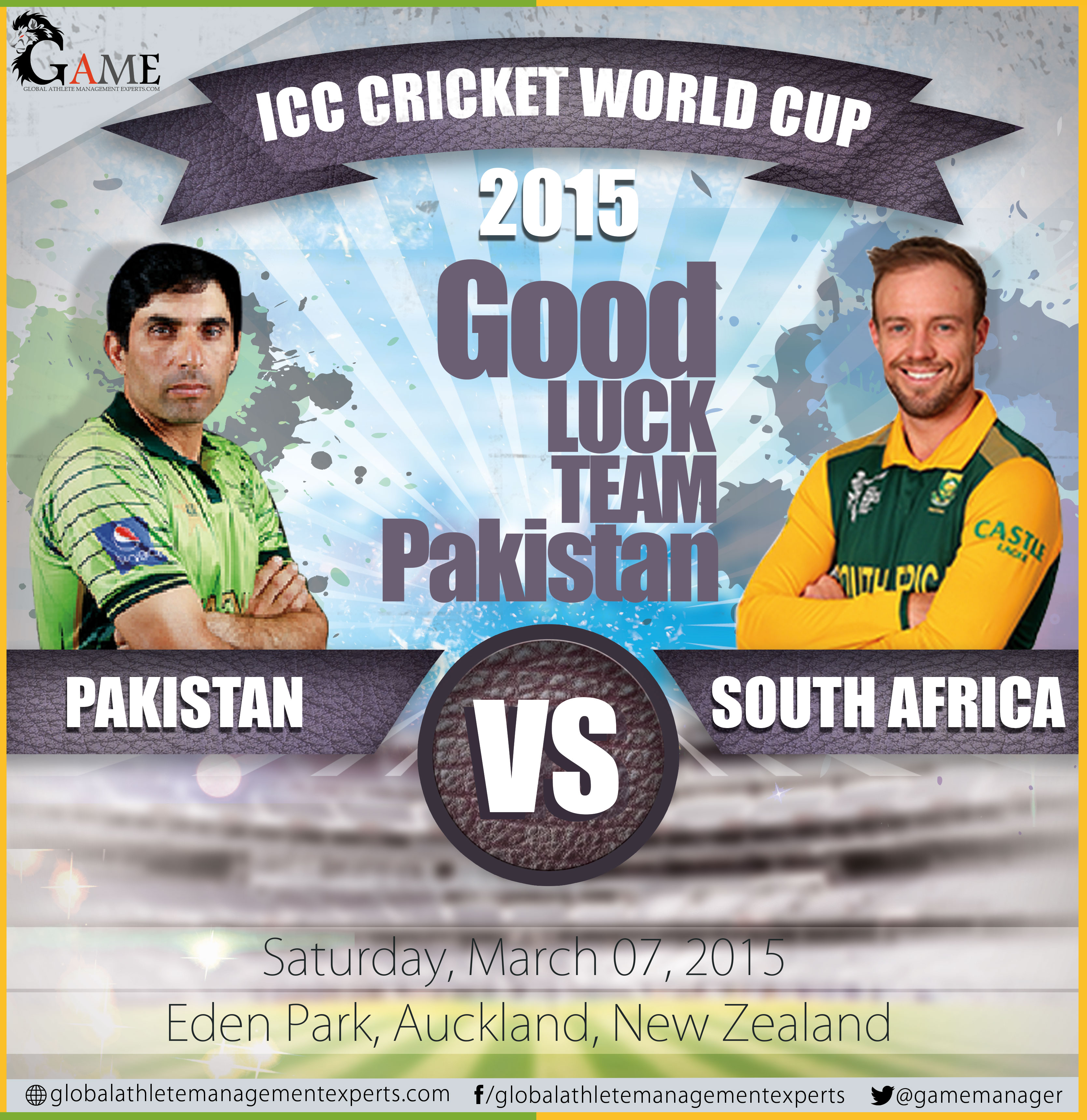

Match Preview: Pakistan v South Africa, World Cup 2015, Group B, Auckland

March 6, 2015

Game’s legendary broadcaster dies in Sydney aged 84

April 10, 2015All Pakistani fans, particularly overgrown boys, have a certain obsession. It goes back to Imran Khan trying to compete in county cricket; it goes back to every adolescent with a tape ball in his hand; it goes back to everything you know and understand about Pakistani cricket. There is nothing, absolutely nothing, which competes with the glamour of being a fast bowler. He is the underdog, the victim and the knight in shining armour – he is what Pakistanis think they are. After all, pace is pace, yaar.

It’s not an obsession with the speed gun, nor with wanting blood on the pitch. It’s just a state of mind. From Fazal Mahmood to Mohammad Asif, speed has never been a prerequisite to being a “fast bowler”. A fast bowler was in your face, he was relentless, and he always thought he was better than you. Asif may never have drawn blood, but he always strutted around knowing he was more than a mere mortal, knowing you were just dirt off his shoulder.

When Osman Samiuddin talked about Pakistan’s haal, it’s about the unpredictability of the team, about how it rides the waves of momentum, but especially about fast bowlers taking the game by the scruff of the neck and not letting go till there was no pulse.

This, sadly, has been lacking in Pakistan cricket for most of the past decade. Since the Asif- and Shoaib-inspired haals of the mid-noughties, Pakistanis have craved the dish they love the most. As that decade wore on, Shoaib and Asif’s fitness and other concerns slowly removed the spunk from Pakistani bowling. And as the ODI game changed in the meantime, Pakistan’s history of improbable bowling-led comebacks started to become exactly that: history. A generation that grew up on the idea that any score was defendable and no cause was lost till it mathematically was, suddenly realised that both the international game and their team no longer possessed that which had made them fall in love with the sport in the first place.

It is why the loss of Asif and Mohammad Amir hurt as much as it did. They were the first drops of rain in the middle of a drought; the expected thunderstorm ended as a slight drizzle. And before you could recover, the clouds parted and the sun shone before the thirst was even quenched. It’s why Salman Butt is never evoked whenever pangs of nostalgia grip a Pakistani fan.

Even with the week-long haal of the World T20, or the spin-led desert demolitions of Team Misbah, the appetite has never been truly fulfilled. It was all well and good clean-sweeping the best Test teams in the world, but where was the glamour, where was the jazba, where was the Pakistanism? In moments of weakness you fretted that those were just stories of a bygone age. That the era of banging your plastic bottles on the stadium seats to create as unique an atmosphere as any was over.

Well, fret no more. In the absence of the four best Pakistani pacers of this generation (Amir, Asif, Junaid and Gul), in the aftermath of the most depressing World Cup build-up ever, Pakistan have found a pace battery that evokes that bygone age. It may be a flash in the pan, it may be another quick shower before the clouds part, but the forgotten appetite has been whetted once again.

In a World Cup where no other team has successfully defended a score of under 265, Pakistan have now twice defended scores of under 240, against teams whose average score in their remaining World Cup matches is in excess of 290. First came Zimbabwe at the Gabba, a ground where no score of under 240 had been defended since haal was last a regular occurrence. Then came the South Africans at Eden Park, a ground where a sub-250 score (in a 45-plus-over game) hadn’t been defended in this century. Sure, Pakistan continue to bat like it’s 1992, but their bowlers are starting to bowl like it’s 1992 too. And that’s not a half bad trade-off.

The cast that produced these epics is like the clichéd cast of any average sports movie. There’s Mohammad Irfan, with his pace and bounce, neither built to be nor supposed to be a cricketer. There’s Rahat Ali, once the embodiment of the drop in talent in fast bowling in the country, now swinging it like a party in the 1960s. There’s Sohail Khan, the forgotten wunderkind, all bluster and muscle and heart. And then there’s Wahab Riaz, the potential superstar who never was, a lightning rod for criticism, now the poster boy for pace, power and Pakistanism.

In an ideal world – where the two Mohammads said no to Salman Butt – none would have made this squad. Two might not have ever donned the Pakistan jersey. In the real world, though, they are performing in a way that wouldn’t have looked out of place if the bowling attack had been led by an Amir with five years of international experience and an Asif singing his swansong.

And atop it all is the man who is probably been the most irrationally aggressive bowling captain in this World Cup (Brendon McCullum excepted). The man who is supposed to be the embodiment of heartless defensiveness has become anything but.

For those (especially outside the country) whose memories of Pakistani cricket still remain fixed in the ’90s, Misbah is the man who is supposed to be the calming influence over a rowdy, mercurial lot. For most of his captaincy, though, his lot has been anything but mercurial. But without his two banned Faisalabadi boys, and after nine months of trying to decipher how to use his understanding of captaincy for the suddenly depleted resources, he has had his eureka moment: if the bowlers are going to bowl like it’s the ’90s again, he might as well captain like that (some might argue it’s his captaincy that has caused the bowlers to bowl like they have, but then we’d just be splitting hairs). Liberated from the shackles that bind him when he is batting he has become the calm father-like figure he was always supposed to be. His body language hasn’t changed, but Pakistan have.

It may still be a flash in the pan, it may still be the murmurings of a patient in a coma. But just for that, for the hope that springs eternal, for the glimpses that keep the lover interested, this Pakistan team has done more than they were ever supposed to. Suddenly the cornered look like tigers again.

By: Hassan Cheema

Courtesy: ESPN CRICINFO